For the past couple weeks on and off (mostly off), I’ve been working on this gradient code. In my previous post, I mentioned my attempts at vectorizing it which resulted in no performance gain in the end. Here, I recount a tale of writing a generic gradient method in a NSBezierPath category. Yes, a tedious story, but this is a blog after all, plus you stand to get some actually-useful, free source code in the end so bear with me. Or, like a kid pouring all the cereal out of the box to get the glow-in-the-dark prize inside, you could, through the power of the scrollbar, skip all this and just grab the code.

So yes, I wanted to write a category to provide a method to fill the path with a gradient. Of course, you need to provide a start and end color but I also thought, why not also provide an angle? I didn’t need to do gradients at arbitrary angles (the only gradients I need right now are vertical) but when writing this stuff, I like to make it generic. When Apple starts using -23.728° angle gradients all over the place, I’ll be ready.

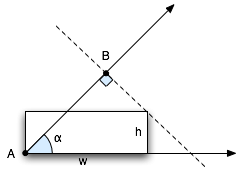

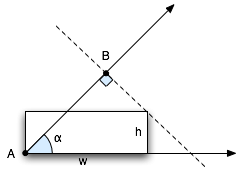

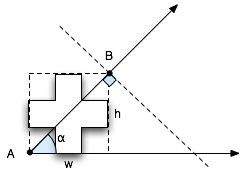

Now, the issue is figuring out the starting and ending points for the gradient given an angle. You want the gradient to fully fill the path. Let’s take filling a rectangle at a specific angle:

In the figure, with an angle α and a starting point A, you’d want the gradient to end at B to maintain the angle and also fill in the opposite corner of the rectangle. Recalling the trig and geometry from the deep recesses of my mind, I came up with the following equation (using known quantities w, h and α):

x = sqrt(h2 + w2) * cos(α - atan(h/w)) * cos(α)

I was a little disappointed that this didn’t reduce down to something a bit more tidy (makes you appreciate E = mc2) but it did seem to work. The problem: not every path is a rectangle. While using the above does cover whatever path may be bound by that box, it is not optimal. Another diagram is in order.

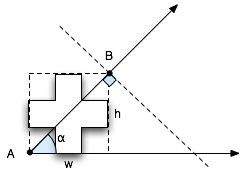

In this example, there’s slop at the start and end. Imagine pulling a squeegee from point A to point B. There’s a gap before you hit the shape starting from A and then a gap after the shape before you hit B. How does this affect the gradient? Why is Mr. Sun sad? See below:

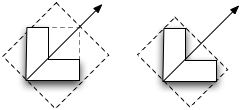

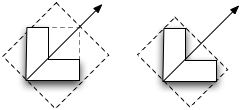

All these diagrams were done in OmniGraffle (except for Mr. Sun which obviously required more sophisticated software). You can see that the “L” shape on the left has a truncated gradient (the black is somewhere where the upper right corner should be). As a user, I’d expect that if I had specified a gradient from white to black, that I would get that range within the shape, otherwise, I would have specified gray as the darker color. It appears OmniGraffle is shading according to the bounding box. Here’s another picture:

The first shape I freehanded with the correct orientation. The second is the “L” shape from the previous diagram rotated. Notice the difference in gradients. It seems to me the user should not need to care how the shape was originally created. The gradient should be white to black in both cases. By the way, I’m not picking on OmniGraffle; I was using it for these diagrams and decided to test it’s behavior in this regard since I had it running. My guess is that this is the common behavior for software implementing gradients with rotation.

If someone specifies an angle and start and end colors, then the final result should be at that angle and have those start and end colors visible in the gradient and not cut off, dag gummit! I feel in the ideal case, you should really be filling the shape with a gradient, not just providing a window to what ever portion of the gradient happens to be lined up under the shape.

The problem here is that we are using the bounding box in the original coordinate system. What would be ideal is to calculate the bounding box in a rotated coordinate system so we can get the minimum span along the axis of the gradient (the line going through A to B in the first two diagrams).

In the case above, we want the bounding box on the right.

My initial approach was to apply the path to the current state, transform the coordinate space to the rotated space and get the bounding box there. The problem with this is that I was getting the bounding box of the bounding box in the original coordinate system. In a sense, I was getting what I originally calculated above. The solution was to transform the path and not the coordinate system.

After some futzing and some stupid mistakes which sent me down some dead-ends, I got it working. Rotate the path, calculate the bounding box and set the start and end points to the edge of the bounding box that corresponds to the gradient axis, then do an inverse transform back on those two points to get them back into the original coordinate system.

What does this get me? Well, for me personally, not much as I mentioned before I only needed to do a vertical gradient. But you, gentle reader, get to enjoy the fruits of my labor. This code is provided under MIT license. If you use it then just mention me and the Noodlesoft site wherever you put your attributions. And of course, if you have any bug reports, fixes, suggestions or whatever, send them my way so I can address/incorporate them.

Noodle Gradient Test + NSBezierPath-NoodleGradient category